I wish this could be one of those “How To Master Mastery-Based Assessment in 10 Easy Steps” posts. But it’s not, for two reasons: 1) I did not master mastery-based assessment, and 2) None of this is easy.

Once my students were on board, I needed to communicate the new practice to the parents. To do that, I had to figure out what I would be doing if I was not going to give numerical grades. I had a few weeks until the new semester started, when I was officially “going gradeless,” but that wasn’t much time to figure out an entirely new assessment system. I needed help.

I went back to Cult of Pedagogy and revisited the episodes on assessment. One of the earliest episodes, “Could You Teach without Grades,” was an interview with Starr Sackstein, a high school English and journalism teacher who was trying something different and had published a book called Hacking Assessment. This book was my bible in the beginning. I read it multiple times. I bought an extra copy to lend people who were interested in the approach (including my assistant principal). The episode also mentioned a Facebook group called Teachers Throwing Out Grades (#ttog), which I joined immediately.

After all of that, I still didn’t know what I was doing, but I trusted my intuition and my students enough to have faith that we would figure it out together.

The best way to understand my initial approach is probably to read the letter I sent to families in which I explained the change to them. I spent weeks on it, not because I felt it had to be perfect but because 1) I needed to clarify for myself what assessment would look like, and 2) I wanted it to be as clear and concise as possible.

Rereading that letter right now, I feel good about it. It is both thorough and clear. Both honest and compassionate. But the part that didn’t sit well with me then—and that significantly contributed to the way I changed things for the 2020–2021 school year—is the part where I equate progress indicators to letter grades. At the time, I felt this was necessary. As I say in the letter, I wanted to err on the side of clarity. My school’s culture is very academically driven and competitive, and I had already experienced too many nightmare-inducing conversations with parents about their children’s grades. I strongly feared leaving myself and my assessment practices open to confusion (and the powerful emotions that often arise from such confusion). So I kept things tight.

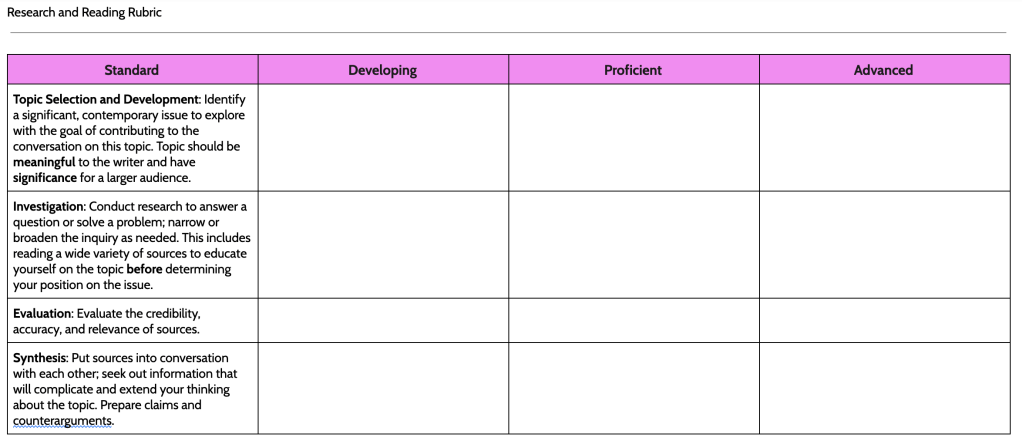

I started redesigning all my rubrics. Much of the advice I had read and received suggested using single-point rubrics to keep track of standards and progress. Here is an example of a rubric I made for the early phase of a research project:

In Google Classroom, I attached the rubric to every assignment and made a copy for each student so that I could enter progress information easily.

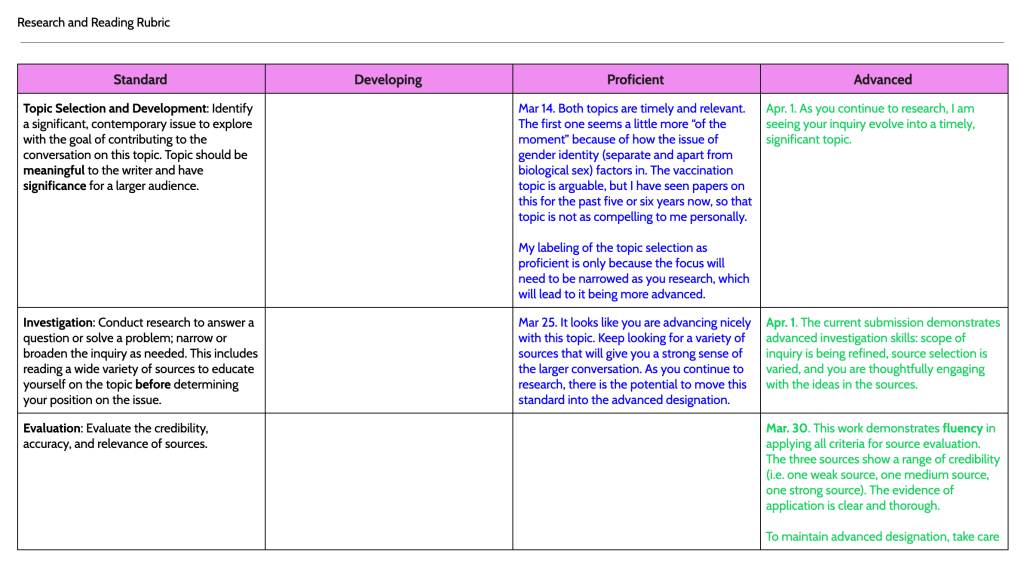

Here is an example of the same student rubric with my comments:

As you can see from this rubric, I determined the initial submissions were proficient. The student revised and resubmitted to achieve and “advanced” designation. So far, so good, right?

In theory, yes. But multiply this by 100 (for the approximate number of students I was working with), and then multiply that by 4–5 (for the number of assignments I gave each quarter), and you have me, drowning in documents and rubrics and resubmissions and conference requests. The students were clearly demonstrating progress. The students were mostly less anxious about grades. But after only a few weeks, I had no energy left to keep swimming.

I knew I needed to simply things somehow, but I did not have time to figure that out. And I did not want to change things on my students yet again. I had faith that I could make it to the end of the year with this process, especially if I gave slightly fewer assignments. So that is what I planned to do.

As it turned out, the universe had other plans.

Stay tuned for the next post: Pointless in the Pandemic.