The other day after class, a student approached me hesitantly and asked if she could talk to me about something. I sensed that it was serious when she noticed that there was still a student lingering on the Zoom session and indicated that she wanted to wait until he was gone to begin. Once we were alone, I sat down to steady myself; I was picking up on her anxiety.

She launched right into it: “I know you have, like, half the school asking you for recommendation letters, but could you also write mine?”

I smiled (which she could not see, but I hoped she could sense ) and started looking in Google Drive for my 2021 rec letter List. At this point, it shows up on my “you open frequently” bar.

“I do have many requests for letters. But it’s not half the school. Just more than half of my students.”

“Yes, but you have a lot of students,” she affirmed.

“I’d be happy to write your letter. And you’re only the ninth person to ask me so far this year.”

She smiled (which I could sense but not see), said, “Thank you,” and rushed out of the room to make it to her next class on time.

I enjoy these moments. I appreciate being asked to write recommendation letters. I am honored that of all their high school teachers, I am one of the people they most trust to represent them to colleges.

But once it comes time to sit down and actually start writing the letters, the enjoyment ends. I feel overwhelmed and bored and regretful that I said yes to so many students. I am often tempted to cut corners, to create a few cookie cutter templates that I could reuse every year: just plug in names and gender-appropriate pronouns. But I never do this because I know this approach ultimately will not serve these students—and there’s no point in doing it if I am not helping them.

I am fortunate to be friendly with a college consultant, Jill Madenberg, who has helped me understand the importance of recommendation letters to students’ college applications. She recently shared the following with me:

Teacher letters of recommendation (LOR) can have a profound impact on an application. Nowadays, with so many colleges going Test Optional, many institutions need to rely more on anecdotal information from teachers who know the students well. Boilerplate language could actually have a damaging impact on a student’s chance of admission. Yet, a detailed, specific LOR that demonstrates contributions to the classroom may tip the scales and help your students gain admission.

Jill Madenberg, Madenberg College Consulting

Jill’s words motivate me to write the best letters I possibly can—while still being honest about a student’s abilities and mindful of my own time. Over the years I have developed a few strategies that help me write original letters effectively and efficiently. Here are some of the most useful.

Create a standard opening and closing. I draft all my letters from the same template, and the opening and closing paragraphs are similar for all letters. I obviously change the students’ names. I also change the adjectives I use to describe the students, based on the reflections I require them to write if they want my recommendation. The introduction should name the student, your relationship to them, and your thesis: why do you recommend this student?

The conclusion then wraps up the letter by reminding the admissions officers of the positive attributes of the candidate while indicating how these attributes will make the candidate successful at the university.

Include a contextual paragraph about your class as well as your school’s learning model in 2020–2021. This kind of information has always been valuable to admissions officers, but it is even more important this year, when secondary schools across the country had different learning models, which obviously impacted not only student learning but also student-teacher relationships. Many of us will be writing rec letters about students we have never met in person; it helps the students for colleges to know this. Discuss some of the challenges that students generally experienced. Then, in the body of the letter, you can be specific about how the student you’re writing about overcame these challenges. And if you feel that the student still struggled, then you can speak about that honestly in the context of your class and the school as a whole. This context can even help you explain why the student’s grades do not reflect their aptitude.

Require your students to write a reflection about their experiences in your class. These reflections are the key to me maintaining my sanity each fall. I cannot remember all the details of all my interactions with the 30+ students I write letters for. The reflections remind me of what I may have forgotten, inform me about what I did not know, and focus my attention on the qualities that the student wants to emphasize: after all, it’s their application. I often pull quotes directly from these reflections to include in the letters.

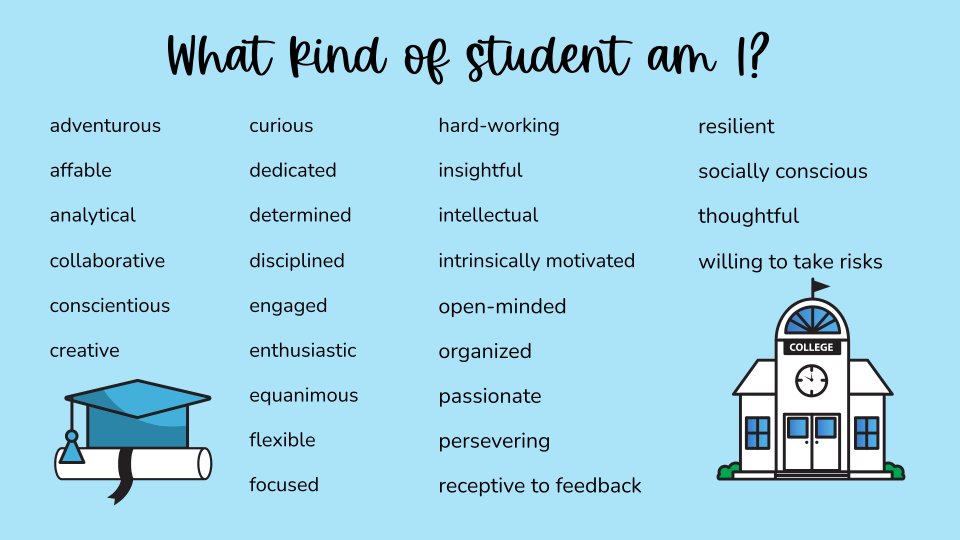

It REALLY helps if you set up the reflection to mimic the structure of the letter. I have two different structures for my student reflections. The first, which I have used for about 10 years, is the “three adjectives” reflection. I ask students to choose three adjectives that they think describe them as students and that can be supported with concrete examples from their experience in my class. Those adjectives then become the thesis for my letter, with each adjective being a body paragraph.

While I have traditionally left the adjective choices totally open, some students might need more support in choosing words that both describe them and appeal to colleges. Here is the list that I give them.

The other structure, which I used for the first time last year, is the “Story of Growth and Resilience” reflection. I love crafting narratives in the rec letters, especially when a student’s experience demonstrates growth and resilience. Last year, I asked my students to reflect in a way that would make it easier for me to tell these stories. This worked very well for the students who overcame significant challenges. It worked less well for the students who were strong all year, so I ended up writing “three adjectives” letters for those students. This year I plan to post both reflections and to let students choose the one that they think will best represent them and their experiences.

A Few Other Tips

- If you use Google Classroom or another learning management system, create a rec letter class or group. This is where I post the reflection assignments; having the reflections in one place helps me stay organized when I sit down to write the letters. This is also helpful for communicating with students in the fall when they are most likely no longer in any of your classes. Hunting them down to remind them about your own personal deadlines or to discuss other issues that inevitably arise is frustrating and time-consuming. Instead, invite them to join the Google Classroom as soon as you agree to write the letter so that you can easily stay in contact.

- Give your students an example of a strong reflection. This can be a challenge because you don’t want to reveal a student’s personal information to other students. One solution would be to write a sample reflection yourself that illustrates what you want students to do. Once you’ve written it, you can reuse it every year. Alternatively, you could create a “mosaic” reflection with pieces from various students, and edit them slightly so the details are not identifiable.

- Keep track of all the rec letter steps in a Google sheet or other organizer. Unfortunately, drafting the letter is only the beginning of the recommendation process. The letters need to be proofread. Some students will have special deadlines. The Common App form must be filled out. And if your school uses a system like Naviance, you have to upload the letters to that system and then actually submit them to the schools on the list (a process that seemingly never ends). If you’re writing more than a handful of letters, you want to keep track of this somehow.

- Finally, do not be afraid to decline the request. I rarely do this, but when I do, it’s for one of the following reasons:

- I’m already writing so many letters that if I take on any more, the quality of all the letters will suffer.

- The student did something unethical in my class (like cheating), and I do not feel that I can write an honest recommendation.

- I cannot comment positively on the student’s experiences in my class. Sometimes students are encouraged to ask English teachers to write letters because they write well, but as I always tell my students, my letters can only be as good as they were in my class.

This year perhaps more than ever before, our seniors need us to write specific, meaningful letters that provide context for the incomplete story their transcripts tell. Our words really can make a difference.

If you are interested in editable versions of my reflection assignments, the adjective list, the Google workflow spreadsheet, or sample letters, please check out this resource on my Teachers Pay Teachers store.