Reviewing my students’ third quarter reflections was one of the most gratifying experiences of my career. I’m looking at them again now to write this post, and I am kind of astounded by the work they did in the reflections, which really only highlights the work they did throughout the quarter.

The key for me was the shift to the visual portfolios. I need to see artifacts. And the portfolios my students created for quarter three were amazing:

These two portfolios were created by good students. But they are also very representative of the work I received from all of my students. In fact, had I assessed the work of these students using traditional grades, they probably would not have scored as high, for a variety of reasons.

One of the most gratifying parts of the quarter three assessment process, though, was not these awesome portfolios. It was the adequate portfolios from the students who—for the first time all year—were realistic about what grade they believed they should earn based on their work. In quarters one and two, I had a handful of students who were submitting work that did not meet expectations and who did not take advantage of revision opportunities. And they always said they earned an A. I pushed back every time, asking, “Where is your evidence? I don’t see A work here.” And finally, in quarter three, they got it. They earned B’s and owned this fact when determining their quarter grades. More importantly, most were starting to push themselves to do better work.

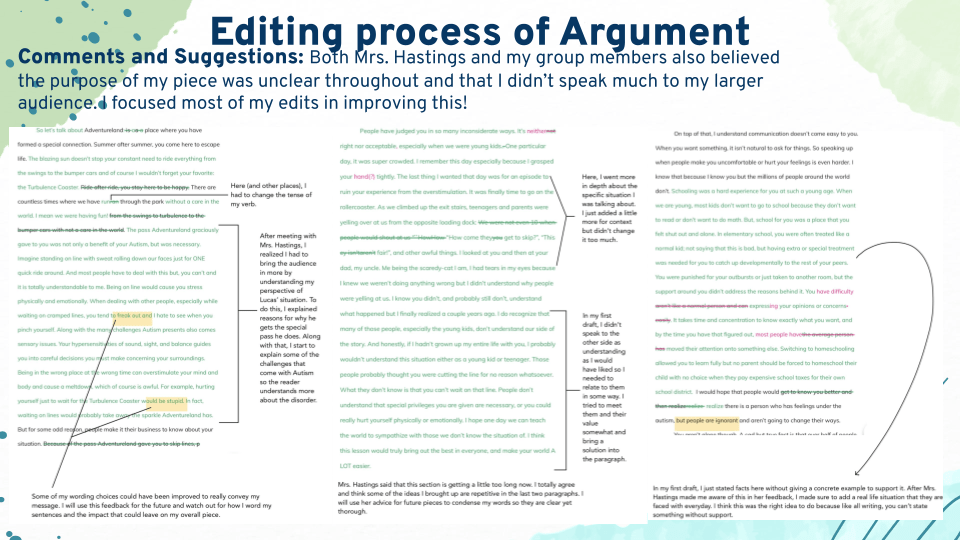

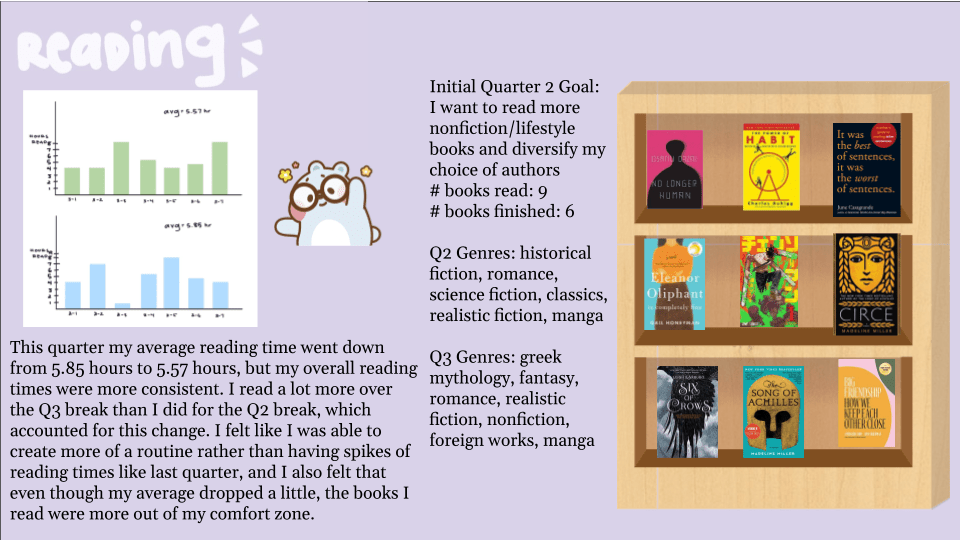

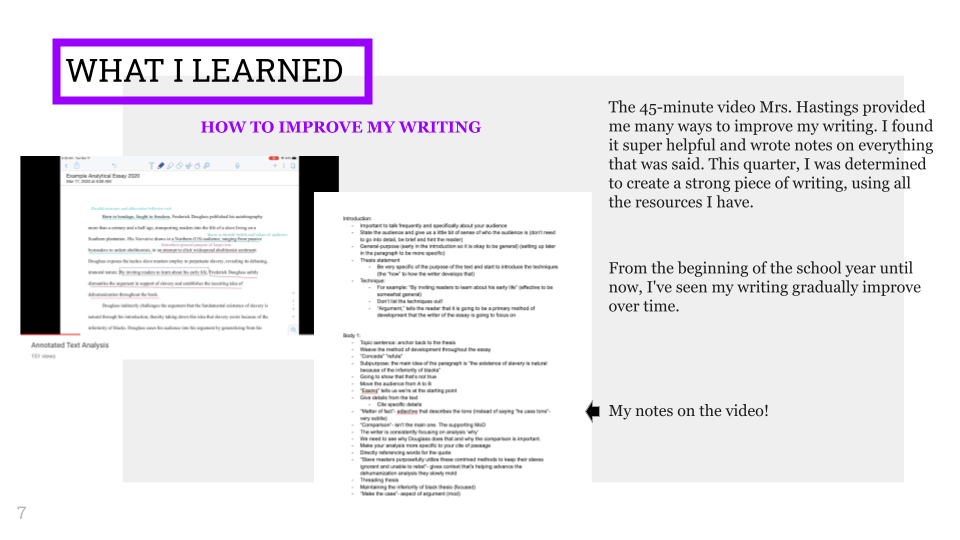

Another significant takeaway for me from the quarter three reflections is how much MORE students accomplish when points are not in the way. When we assess with points, we motivate students to reach a numerical goal. The upper limit is set. They ask, “Is this being graded?” and if we say, “No,” they often don’t put the work in. For writing especially, they look at the rubric, do what they have to do for an A, and call it a day.

But when we don’t give them points on assignments, they soar. They do MORE than the work—sometimes because they are intrinsically motivated and sometimes because they know they get “credit” for everything. In one of the example portfolios above, the student included evidence of several competitions she entered. In the past, I encouraged students to enter competitions, but I never offered points for it, so they rarely did. Because my students are stretched so thin, they often don’t feel that they have time for anything that won’t earn them points. Another simpler example are the notes my students included in their portfolios. We probably all expect our students to take good notes, but we don’t have time to collect and assess the notes. When we invite them to share their notes as evidence of learning and engagement, we motivate them to take good notes and give them a return on their time investment. Here are a few examples of notes some students included in their Q3 reflections:

Now you might be thinking, “But what if my students don’t work that hard, aren’t intrinsically motivated, would never be able to create that kind of reflection?” I have a few responses to this:

- What makes you so sure they can’t or won’t? We constantly make judgments about students because this is part of our job. But these judgments are often limiting and can even become self-fulfilling prophecies. What if, instead, we told our students, “I know you are capable of this level of effort. I will support you. But you have to step into the challenge.” Then give them examples of great work other students have done. Show them what success looks like. You could even co-create the success criteria. Expect more from them, and they will usually rise to meet your expectations.

- Perhaps reflect on where these assumptions are coming from. By the time students are in high school, they have already been boxed into a “type”: the good student, the intellectual, the “doesn’t work to potential,” the hard worker who always struggles. One HUGE problem with these labels (aside from the obvious damage that the negative labels cause) is that they have been created based on traditional grading practices—which we already know are harmful. What if you started the year by inviting students to redefine themselves and their learning identities? To show what they know and are capable of in a way that works for them?

I will be the first to admit that part of my success with pointless assessment is because I work with highly motivated, highly capable students. But I also believe that if we are clear about our expectations and provide students with the support they need to meet them, they will. No kid wants to be a “bad student.” Sometimes they just don’t know how to be a good one. So let’s show them.