High school is where most students’ love for reading goes to die—if it even stays alive that long. Many factors contribute to this, but one of the biggest is that in high school (and often even earlier), reading is not something done for fun but something done for grades. Instead of “read this book because you will relate to the main character” it becomes “read this book because there are assignments attached to it.” Reading very quickly becomes associated with the stress of school, another task that must be completed as quickly as possible—which often means finding ways to complete the assignments without actually doing the reading.

Regardless of our approach to teaching reading in high school, the above description probably sounds familiar to most secondary English teachers. We know most of our students don’t enjoy the books we give them. We know they don’t get much (besides stress and frustration) from the questions, tests, and essays that always accompany assigned reading because we teachers need something to measure and motivate. Perhaps most disconcerting, we know they don’t actually read—and yet we continue to accept their fake reading because we genuinely don’t know how to solve this problem.

I fear that it sounds like I am judging English teachers for their complicity in killing their students’ love for reading. And to be honest, I am a little bit—and this includes a large amount of self-judgment because until recently, the approach outlined above was the one I used. I assigned books from “the list” (and yes, the list is mostly dead white men, with a few people of color and women sprinkled in), required annotations, and wrapped up each novel with an essay. For many years, I felt pretty good about these practices. Annotations require thinking and are harder to cheat on than guided reading questions. Essays help students develop a variety of critical thinking and writing skills while giving them some freedom of choice regarding their topic selection. And even though I encouraged students to also read books of their choosing, I did little to help them with this, and I always accepted their reasoning for not doing it: “I just don’t have time to read books for fun anymore.”

To be clear, I do still see value in many of these practices. Students need to think about what they’re reading, and they need to demonstrate that thinking somehow. Otherwise, we teachers can’t help them improve. I do teach analytical essay writing. It’s just no longer the only type of writing we do. And I don’t blame teachers for adopting these practices because so many factors outside of our control—including the standardized testing industrial complex—force us into practices that we do not always believe in.

But sometimes we just need a little help to find another way: a way to rekindle a love for reading that still provides opportunities for teachers to measure progress, guide skill development, and create the rigor that we believe is necessary for high school English.

I had a lot of help in developing my current reading pedagogy. I have been profoundly influenced by the work of Penny Kittle (Book Love; 180 Days) and Kelly Gallagher (Readicide; 180 Days). Their work showed me another way when I was ready to see it. What follows is the structure I have built in my own classes based on the foundation their work has provided.

Ingredient 1: Motivation

I am a why person. I need to understand the reasoning behind anything I am being asked to do. If I agree with it, that’s often all the motivation I need. Many of our students are this way, too, so I always start with why.

I introduce the possibility of reading differently by inviting students to openly and honestly discuss their experiences with reading. I kicked off that conversation by asking them to respond in writing to the following passage from Disrupting Thinking by Kylene Beers and Robert Probst:

I then had them discuss their responses in small groups while I listened in. Their conversations were thoughtful, energetic, and loud. They had so much to say: how they liked reading until they were assigned their first outside reading project in sixth grade. (They could choose their own books, but they had to write an essay for everything they read.) How stressful reading was because while they were reading, they were just worrying about which details they might need to remember for the next day’s reading quiz. How annotating pulled them out of the stories and made them read only through the lens of essay writing. How reading is associated with school and work, and so this is not something they would choose to do when they had free time. They’d rather watch YouTube or TikTok because they needed a brain break.

I wrapped up the conversation by offering a compromise. “We’re going to approach reading differently in here,” I said. “You will have choices and there will not always be an assignment attached to your reading. But this is still English class, and I’m not doing my job if I don’t help you keep track of your progress, figure out what you need to grow, and help you get there. You have to read and there will have to be evidence of that reading. But we can do it differently if you agree to do your part.” Intrigued by this promise, they agreed. (Even if they weren’t—yet—excited about reading, they admitted it sounded better than what they were used to.)

Ingredient 2: Individuality

For an independent reading program to be successful, we must meet students where they are in terms of both their skills and attitudes towards reading. To do that, we must find out where they are. And the best way to do that is by asking. I give students a reading inventory early in the year. I encourage them to respond honestly because I can’t help them if they tell me what they think I want to hear. The reading inventory asks a variety of questions about their attitudes towards reading, their reading habits, and their genre preferences. (If you would like an editable version of the one I use, it is available here on my Teachers Pay Teachers store.) I refer back to their responses throughout first quarter as I help them set reading goals and find books they will enjoy reading.

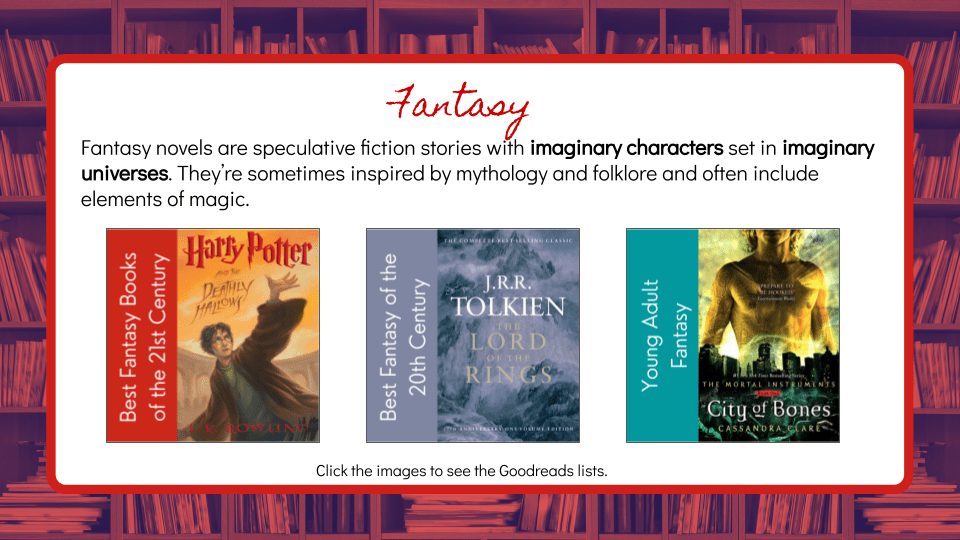

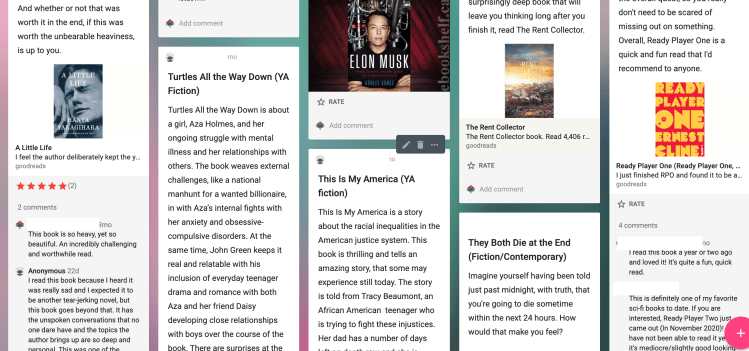

I also encourage my students to embrace what they already enjoy. If they are going to be successful in creating a reading routine, they need to be excited to open the book. I provide support through personalized recommendations and curated lists from Goodreads. If you aren’t familiar with Goodreads, it is an incredible reading resource. I invite (but do not force) my students to become friends with me on Goodreads so they can access my recommended reading shelves and observe as I model my own reading life. The Listopia community-created reading lists are an amazing feature, and these are what I use to create my own curated resource. To help my students navigate the potentially overwhelming number of lists on Goodreads, I give them a slideshow (available here on TpT) that defines the most popular genres and links to Goodreads lists for each genre. Here are a few example slides from that resource:

Ingredient 3: Excitement

Helping students see the possibilities is part of building excitement around reading. The book genres and reading lists resource is only the beginning of that process. After I introduce Goodreads, I give students a “Next Reads” Google doc where they write down the titles they are interested in reading. (They can also keep track of this with Goodreads’ Want to Read feature, but I require the Next Reads list because it’s easier for me to access.)

If you’ve ever kept your own “To Be Read” list, then you know how motivating it is. Seeing all those books waiting to be read makes us want to read more. While I don’t want students to see this list as a to-do list they must complete, the list is a reminder that there are books out there they will enjoy spending time with. These lists are also crucial for momentum: one of the reasons students don’t read is because they don’t know what to read. If they finish a book and don’t know what to read next, they are likely not to read at all.

Regular book talks are another way I build excitement around reading. I try to do at least three book talks a week. I start with my own “five star” books, things that I have personally loved, so that my enthusiasm for each text becomes contagious. As the year progresses and students become more comfortable choosing their own books, I invite them to do the book talks. Giving a book talk becomes a goal for most students, and it’s the best way to help them find books they’ll love. Most people get book recommendations from people they know and trust, so class book talks are a natural extension of this process.

Ingredient 4: Honesty

It would be great if this one could go without saying, but it can’t. In many ways, honesty is what we are trying to reclaim when we emphasize independent reading in our classrooms. Many teachers believe that they cannot trust that students are actually reading their books if everyone is reading something different. But many of them weren’t reading the books anyway. If we give them some agency over their reading selections, they are more likely to actually read the books. But this is true only if we create the conditions under which a variety of reading preferences, habits, and practices can be considered successful. It is true only if we allow them to be honest and reward them for honesty rather than punish them for not meeting every expectation. . . .

Ingredient 5: Safety

. . . which is why safety might be the most important ingredient. Students won’t be honest unless they feel it is safe to do so. They have been raised in a carrot and stick system in which they are rewarded for appearing to have read and punished for actually reading but not remembering everything they have read. They are punished for disliking reading, for not reading enough, for not understanding everything, for not reading hard enough books, for abandoning a book they don’t like. So they have learned ways to avoid these punishments, which often involve cutting corners. If we don’t want them to do this, we have to use a different system.

I make honesty safe in a variety of ways. First, I talk about it all the time. I talk about how I abandon books or forget details or don’t always have time to read. I promise that I won’t shame them if do these things, too. And I continually follow through on this intention, thanking them for their honesty whenever they admit to anything that they might be uncomfortable telling me.

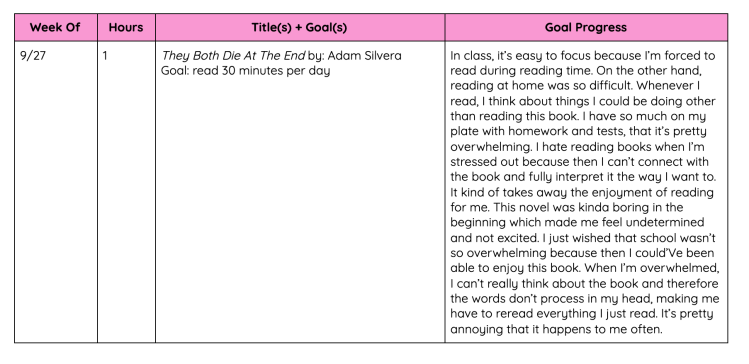

I also don’t give them points for their reading. People who have been following this blog know that I don’t give points on any assignments (it’s kind of the theme here), but I think it is worth discussing specifically in the context of independent reading. To collect reading data, I ask students to log the time they spend reading each week and to reflect on both the book and the process of reading. I tell them early on that I expect them to read a minimum of 2 hours each week. But sometimes they don’t, and that’s ok. If they never meet the 2 hour mark, then we talk about what might be getting in their way. This will likely have some effect on their quarter grade, but it’s not fixed in an unforgiving structure. What’s more important is their willingness to try new strategies until we figure out what will work for them.

If you grade with points because you have to or because you want to, then I encourage you to make the reading logs low-risk by having them be a low point value and giving the students credit for submitting something regardless of what the data shows. For example, if one student reads for 10 hours and another student reads for half an hour, they both get five points for submitting an honest weekly reading reflection. Otherwise, they’ll lie. And you won’t know what’s getting in their way, so you won’t be able to help them figure out how to develop a reading life. And they won’t become readers.

Ingredient 6: Time

It’s no surprise that the most frequently cited reason for not reading is not having enough time. Time is the most valuable resource most of us have—because there is never enough of it. So as teachers, we have to make tough decisions about what we value and then make sure we are using our precious class time to practice those values. If we believe that creating life-long readers is important, then we must invest time into teaching students how to do this.

This means we must devote some class time to choice reading—and not just the book talks. We need to give students time to read during class. This can be hard to do. When we’re in the middle of a research unit and it doesn’t seem like students are mastering the skills, we will be tempted to cut reading time. But doing so just reinforces the message that reading is expendable: It’s the thing we can cut when other demands creep in. And while the reality is that sometimes other demands are more pressing, we don’t want reading to be the first thing that students always cut out of their busy schedules. Instead, we must teach them to make time for reading—and this starts by making time ourselves.

One of the ways I did this was by cutting back on the number of whole class novels I required. I think last year I did two with my ninth graders and one with my juniors. And everyone read at least four times as many books as they had in previous years when I did more whole class novels. Because they were expected to. Because they wanted to.

I also help students learn how to make time for reading. I tell them it’s homework; I will let them choose the books, but they have to keep their part of the bargain by spending some time each day reading. I also give them this article by John Spencer and ask them to set some reading intentions based on these ideas. There are many creative suggestions here, like putting a reading app on your phone home screen and leaving books around the house to remind you to pick one up when you’re bored. And the suggestions work—especially when we give students agency to choose and create their own strategies. So many of my students have reported that cutting down on social media to increase time for reading has helped their mental health, their sleep, and their feelings of self-worth. But I couldn’t tell them they had to do this: they had to decide this for themselves.

Ingredient 7: Accountability

I’ve talked a lot about safety and honesty and excitement, so you might be thinking, “This sounds fun but also really fluffy. Where’s the rigor?” And the answer is, it’s wherever each child needs it to be. The students must read if they want credit for the course. This is non-negotiable. But what they read is up to them. And most students want to challenge themselves. Even if they begin the year reading only YA fantasy novels, most of them will choose at least a few more challenging books later in the year. The key here is that they are choosing. I can distribute The Great Gatsby and require everyone to read it. And some of the students will read it. A few of them will enjoy it. But if I just put it out there as something they might want to consider reading at some point, those who choose it will actually read it and will be more likely to enjoy it.

So how do I know they’re reading? That they understand what they’re reading? I ask them. The weekly reading reflections are a constant point of communication between the students and me. They not only tell me what they’re reading and how long they’re reading, they also tell me how they feel the reading is going. Early in the year we do minilessons on monitoring for comprehension, so the students are learning how to tell for themselves if they understand what they’re reading. This is the skill they will need to be successful in college and beyond.

I also have regular reading conferences with students during the time that students are reading independently. It usually takes me about 5 minutes for each conference, so if the students have 10 minutes to read, I can talk with two people. If I meet with 6–8 students each week, I can meet everyone in about 4 weeks. It takes a while, but this is a valuable practice. Hearing the students talk about their reading gives me a better sense of their progress and where they might grow next. And because they know they will be having a reading conference at some point, they know they need to be ready for it—which means they have to read.

Each quarter, I also ask students to choose one of the books they read to do some deeper thinking around. This is not an essay assignment. I usually suggest they do a sketchnote or two-page notebook spread of their thinking. They submit photos or PDFs of these pages, and I review them to evaluate how deeply they are thinking about what they are reading. This thinking continuum is really helpful for moving student thinking forward.

I think it’s important to ask the students to think about their reading but not to require substantial assignments too frequently, as these get in the way of their momentum. If they know they will have to do an assignment for every book they read, they won’t read as many books.

Ingredient 8: Flexibility

Flexibility is closely related to accountability. We need to know that students are reading, and we need to see how they are developing as readers, but we need to let the students have a significant say in how these things are done. I encourage my students to come up with their own ways of demonstrating their thinking about their books. I encourage them to find their own ways to step out of their reading comfort zones. And I encourage them to follow their instincts. Progress is not a straight line. An authentic reading life will include some “dessert” reads and “brain break” books. This is not just ok—this is necessary. If we want our students to be life-long readers, they need to see the value in all kinds of reading material and not feel shame about reading something “light.”

We also need to teach them to be flexible with themselves. Some of them want to create really rigid reading schedules, which can be helpful, but if they’re too rigid, the students often see the inability to maintain the schedule as failure. But it’s not failure—it’s life. I try to shift them away from rigidity into intention-setting: “This week, I intend to read for 20 minutes each day after dinner.” If they miss a day or two—or all seven days—they didn’t fail. They just need to reflect on why this happened and revise or reset their intentions. Eventually, they will figure out a routine that works for them. Most importantly, they will learn how to get back into reading when life gets in their way—which it will.

It really comes down to this: If we want students to read on their own, we have to let them read on their own.

Ingredient 9: Community

My favorite part of the independent reading approach is the reading community we create. Once we get started talking about books, we never stop. We are always talking both formally and informally about what we’re reading. Students walk into the room with their noses buried in books, and we all want to know what they’re reading. They form book clubs with their friends. They share their favorite titles through book talks. We also have a recommended reading Padlet, where students write reviews of books they’ve enjoyed. I post what I’m reading on Instagram and invite my students to follow me. We even started a reading hashtag at our school.

I was tempted to add another ingredient to this list: joy. But joy doesn’t have to be added to the recipe. If these ingredients are there, then joy is what is created. It’s the scent that invites you into the room and makes you want to stay there. It’s the feeling of biting into something rich and satisfying. It’s the taste of accomplishment, independence, and book love.