First quarter we laid the foundation; by second quarter we were ready to frame out what we were building. We were not only learning about learning and ourselves but also developing skills and content knowledge. I had a rough blueprint in mind—arguments for the juniors, literary analysis for the freshmen, narratives for everyone—but I did not directly communicate this to my students when we were setting goals. And even if I had, they probably wouldn’t have known what to do with that information. Though I did not know it at the time, I was setting us up to construct a neighborhood without a clear design aesthetic. The houses would get built, but they would vary significantly in quality, shape and size.

At the beginning of quarter two, the students set goals based on what they had done the previous quarter—which made all the sense in the world from their perspective. Although I looked over their goals, I didn’t worry about discrepancies between their visions and mine. I wanted them to have their own goals for intrinsic motivation.

For the most part, this all worked out. Most of the students understood that if I left feedback suggesting improvements on a piece of writing that they should revise it. I continually encouraged conferences and revisions. What I did not do—a mistake I will never make again—was set firm revision deadlines. In my mind, being proactive about revision was an approach to learning that I wanted students to be accountable for. If they put revising off until the end of the quarter, then that choice would need to be part of their quarterly reflection and considered when determining a quarter grade. But in their minds, “She didn’t give us a due date, so I have until the end of the quarter.” So there I was again, staring down a sizeable stack of revisions at the end of the quarter. Although I had said, “I will not suffer because you made the choice to put something off,” it happened anyway because I did not create the boundary necessary to prevent it. Lesson learned.

For the quarter 2 reflection, I wanted something much more thoughtful, creative, and detailed than I asked for in quarter one. So I designed this assignment:

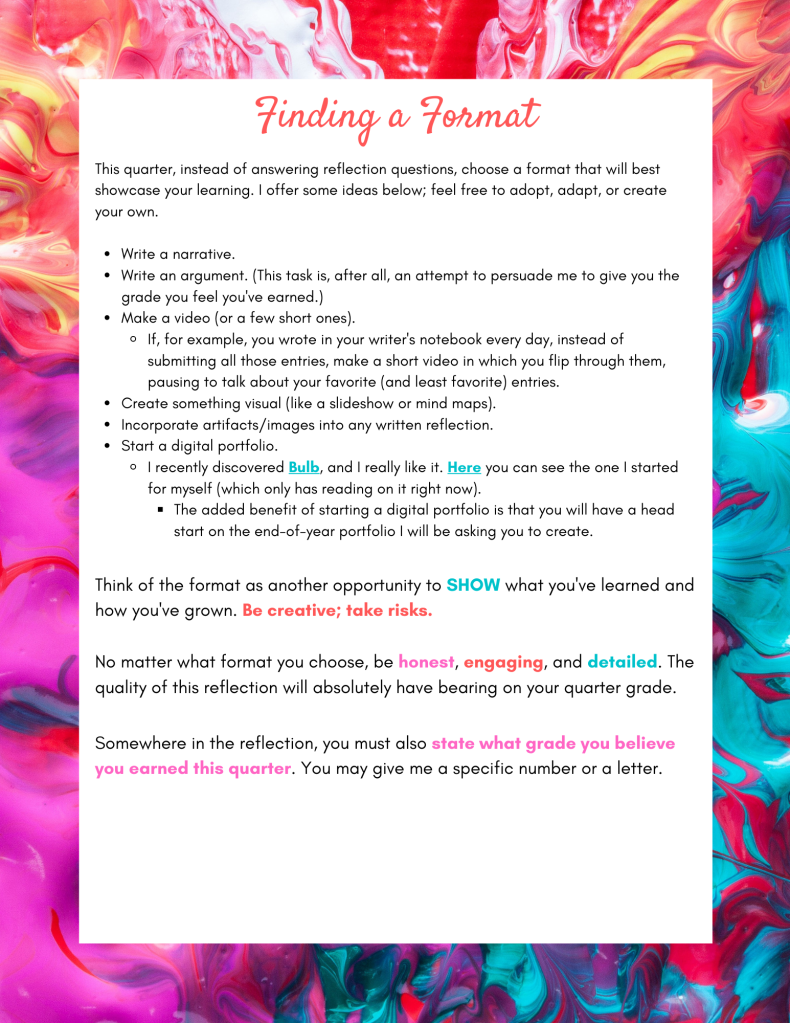

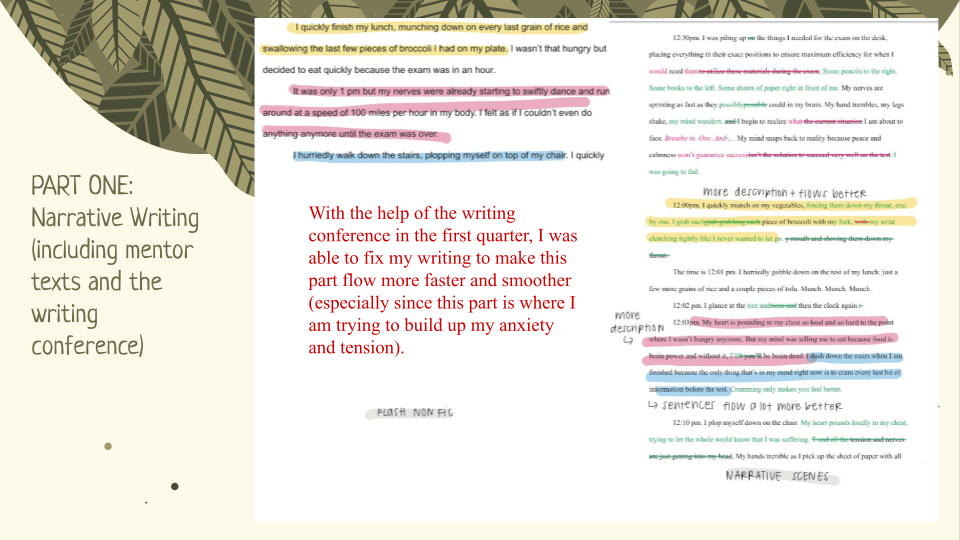

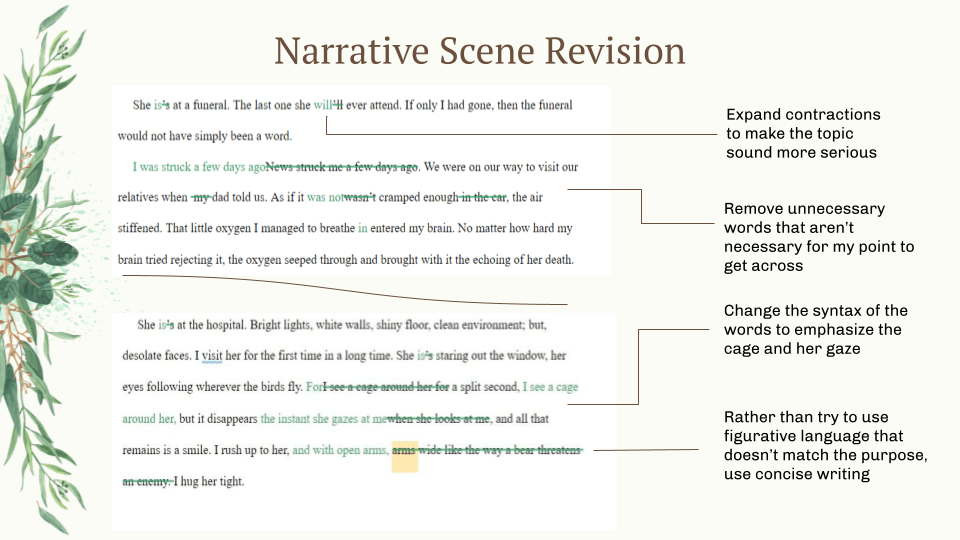

As often happens when I give students freedom to create, many of them blew me away. I received Bulb portfolios with thoughtful and thorough evidence of and reflections about revision. I received Google slideshows with reading comparison graphs and screenshots of annotated mentor texts. Some students made video reflections. One student even wrote a play. These were the wins.

There were fewer losses, but those were what both my students and I learned from most. A few examples:

- One student created a very long video with lots of examples of all the ways she went “above and beyond” with reading, including showing me some artwork she had made. She did not revise any of her writing, even though I had specifically said, “You need to revise this.

- Another student set a goal to write in her notebook regularly. For her quarterly reflection, she created a video in which she read me three of these entries; that was the only evidence she provided. She did not attend a single writing conference or revise a piece of writing. She said she thought she earned an A.

- One student only included reading growth in his reflection and said he thought he earned an A. When I asked him where the writing evidence was, he said, “I think I only improved in my reading this quarter, so I didn’t include writing.” I responded, “But the writing is still part of this quarter; it needs to be part of your learning story.” He hung his head in shame.

So how did I deal with all of this? I left video feedback for everyone. I wanted the students who hit home runs to know exactly what they had done well; I wanted the students who struck out to know exactly what they would need to do next quarter to improve. I went through all of my data and made my own arguments for the grades I thought each student deserved. In about 20% of the cases, I gave students substantially lower (at least half a letter grade) than they had asked for. Not a single student argued with me. The process was incredibly frustrating and draining, but it did pay off in the third quarter (more details in the next post).

I learned a few other valuable lessons as well:

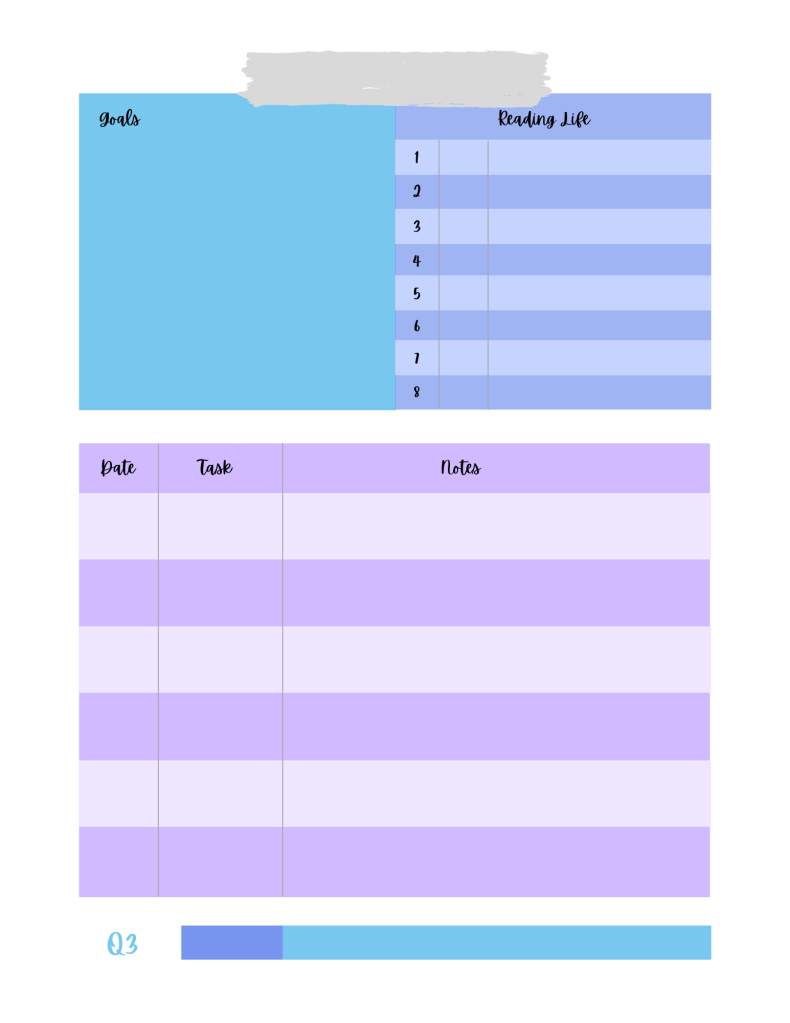

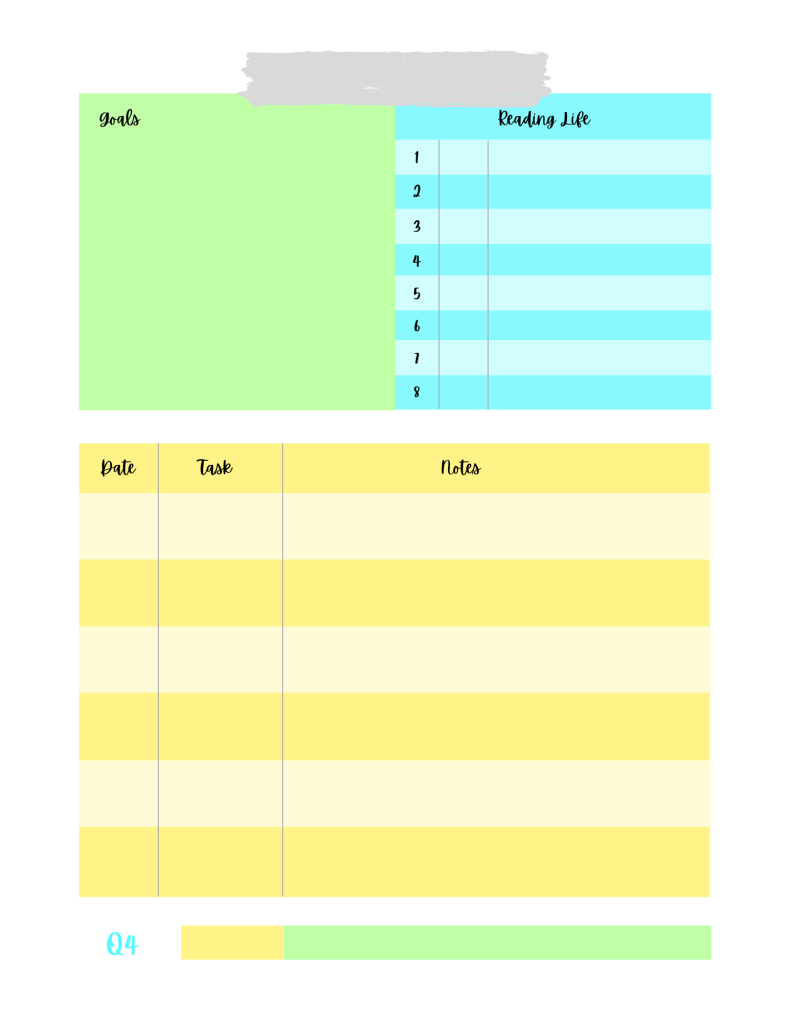

I REALLY like visuals. So I took what worked for me and redesigned my quarterly reflection assignment. The day that I returned their quarter two reflections, I reviewed this slideshow with them and asked them to collect artifacts all quarter that they could use to create something similar for quarter three.

Here are a few examples from that slideshow:

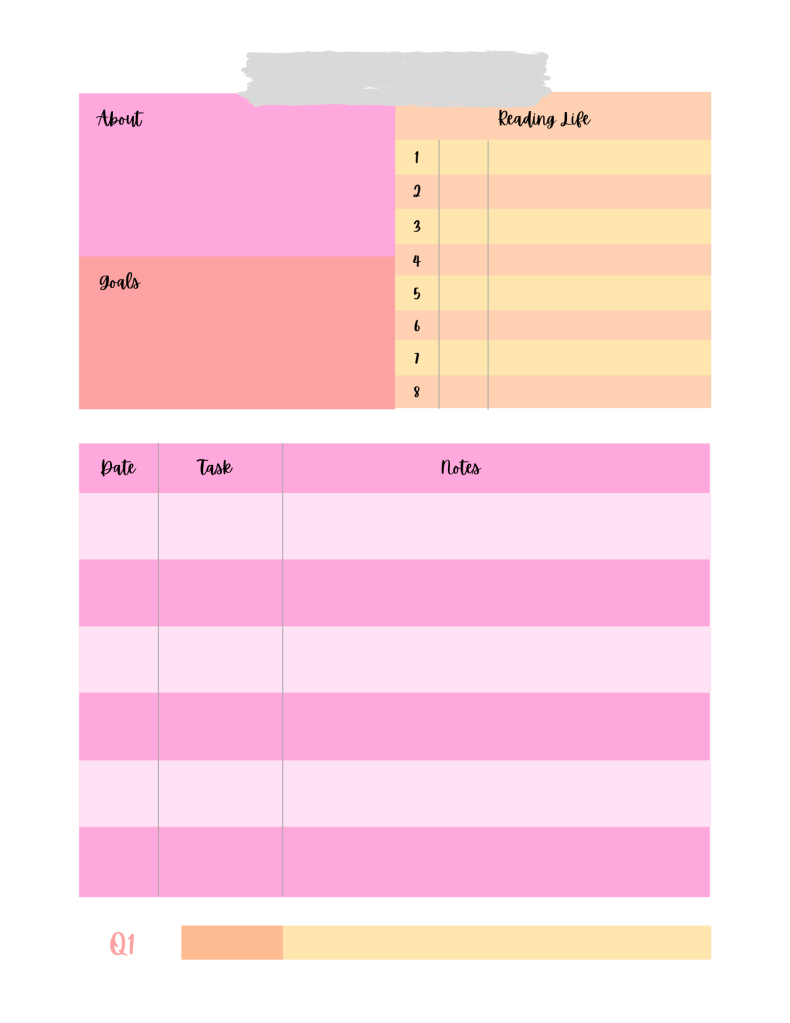

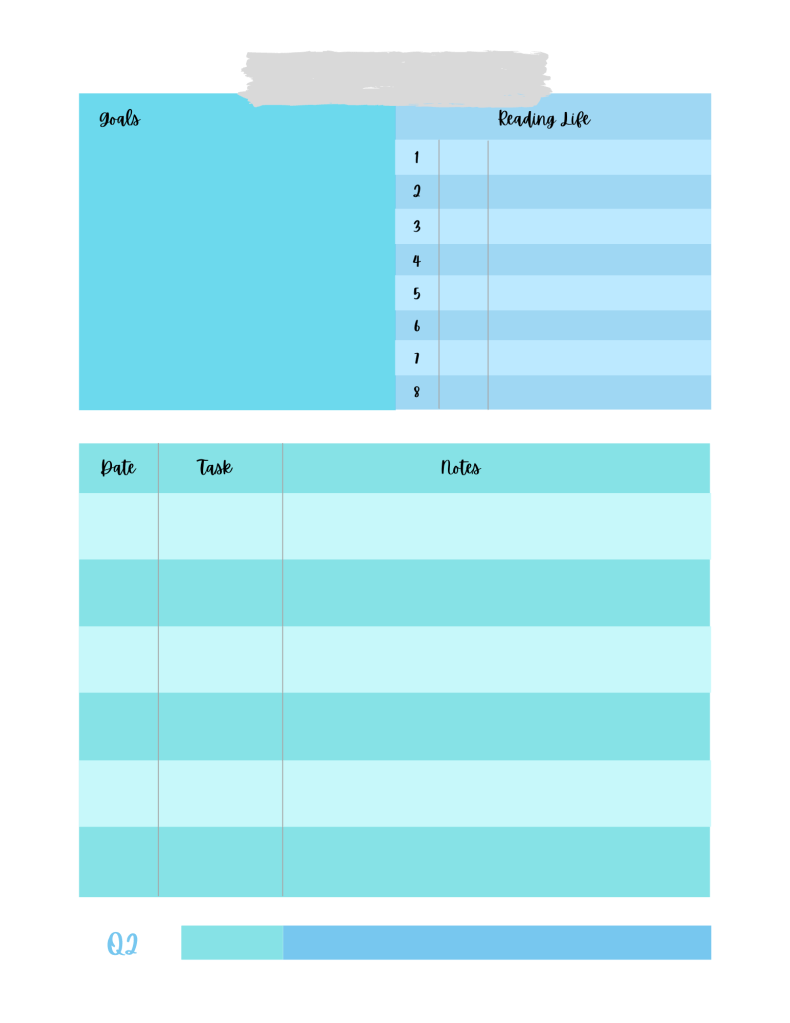

Traditional gradebooks are not helpful when you aren’t giving traditional grades. Shocker, I know. While I have been able to input words instead of numbers into my district’s LMS, this information is not easy to comb through. I need to be able to see the comments for each assignment, but to do this, I have to separately click on each one. What I really wanted was a gradebook with a page for each student so that I could see each person’s work all at once. The student reflections helped with this, but I could not rely on every student to tell me everything; I needed to be able to cross-check their claims with my own evidence. So I made my own gradebook: a disc-bound notebook with a page for each student. This took a while to set up, but it saved me substantial time when I had to do third quarter grades.

I liked it so much, in fact, that I designed a template that I could print out and use next year.

Fourth quarter, however, I experimented with a digital notebook that I like better because of the flexibility it offers to change things easily and to copy and paste. Looking at the PDF version of the print notebook now, I still love it—the design makes me want to use it. But I’m probably going to keep iterating the digital gradebook for the sake of efficiency. I will share those ideas in future posts.

Hello! What a marvelous blog! After 3+ decades of knowing grades were holding my students back from what they might actually be achieving, I discovered Sarah Zerwin’s empowering book and now this blog. Thank you for sharing your thought processes and products. You mention in this post that you created a digital notebook in which to record student progress, one page per student. Could you describe in a bit more detail what has worked for you in this regard?

Thank you!

Deb

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Deborah, thank you for the feedback! I can definitely help more with the digital gradebook. I am actually going to make a post (probably next month) that goes into it a little more, and it will have links to a few examples/resources. But in the meantime, I have a Google slideshow with a slide for each class. Each slide has a table with all the names of the students in that class. And those names link to a doc that has that student’s data. (Which usually has links to their actual work.)That way I can see all the details for one student at a time (as opposed to traditional grade books where you mostly see one assignment at a time or just an overview of the student).

I am thinking I will even do a video demonstration because it’s probably hard to visualize what I’m talking about. If you want to get notified when that comes out, I suggest subscribing to the blog.

Thanks for reaching out!

LikeLike

I will also be publishing updates to my Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/mindfulenglishteacher

Thanks!

LikeLike